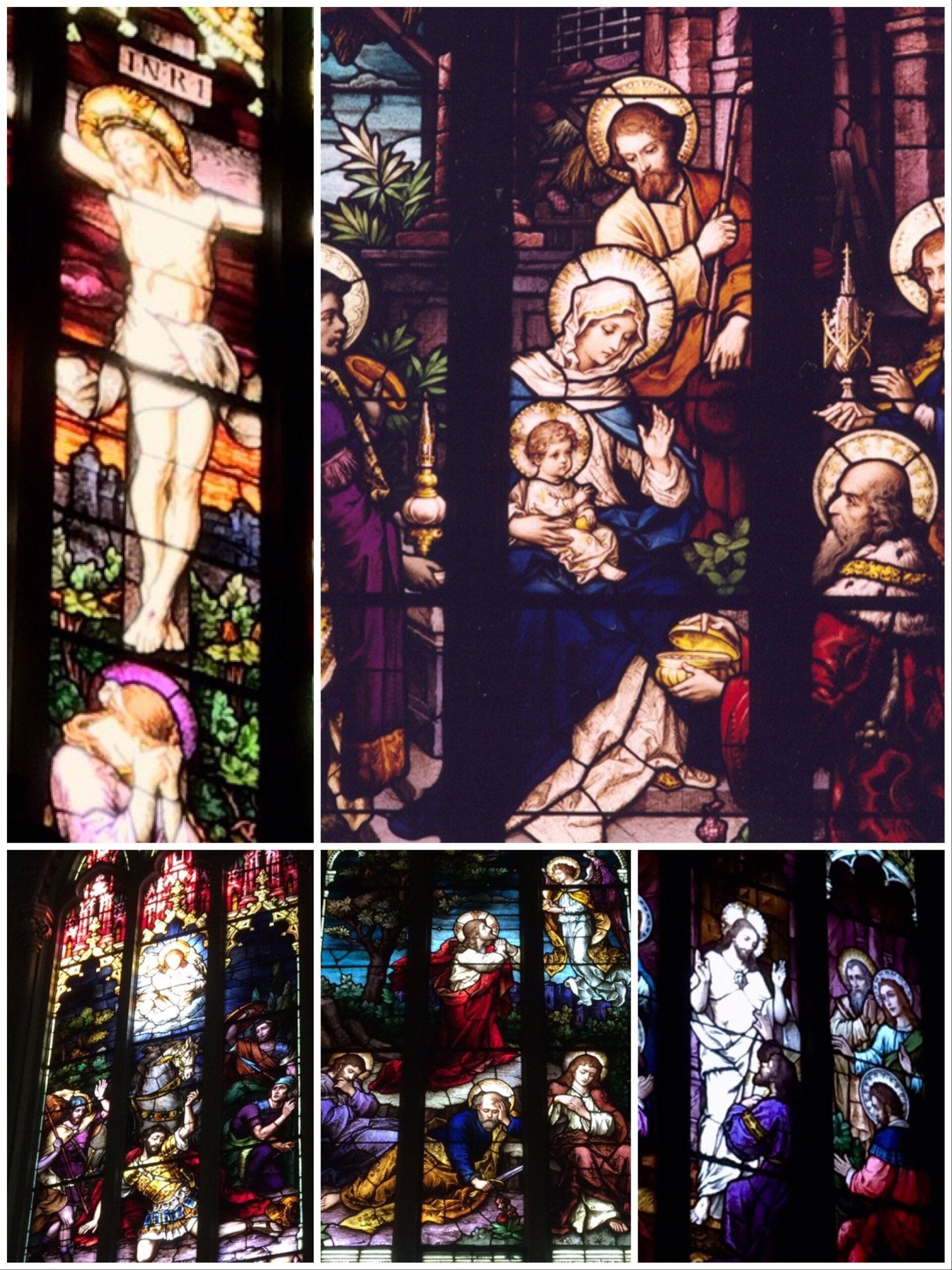

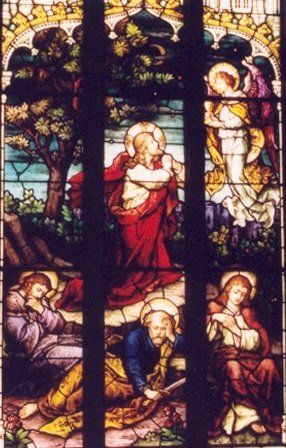

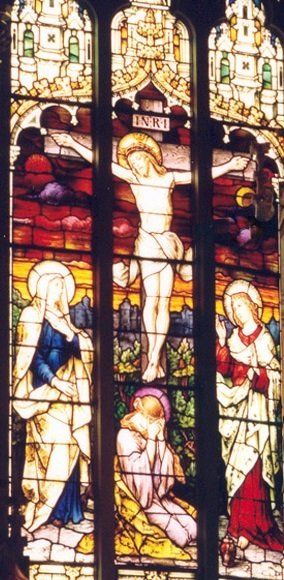

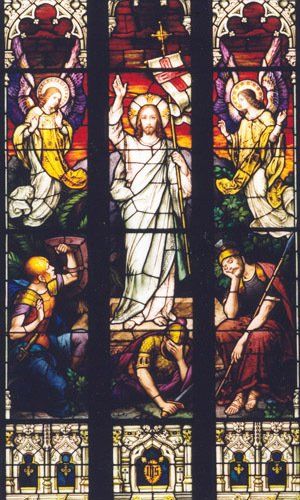

Our Historic Stained Glass Windows

produced by Mayer & Zettler, circa 1900

St. Paul’s: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

Stained Glass Window Restoration

conservation and restoration work provided by

Building on our past to preserve our future

Bishop Riordan's Stained Glass Legacy

By Gail J. Tierney

[Editor's note: The Bay Area is filled with churches that contain magnificent stained glass windows, which we often take for granted. Gail Tierney, a Ph.D. student in the History of Art and Religion at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, takes a closer look at two of the most important producers of stained glass in the history of the Archdiocese of San Francisco.]

"These images nourish faith and commitment in the unique manner that art offers us a prism through which the material world reveals the presence of God." Bishop Carlos A. Sevilla On Sunday, January 11, 1891, as Archbishop Patrick Riordan dedicated the new Saint Mary's Cathedral on Van Ness Avenue and O'Farrell, a dazzling array of prismatic light flooded the interior. Daylight had turned into a variegated, illuminated light, as it passed through the intricate, multi-faceted stained glass windows produced by the Franz Mayer Studios of Munich, Germany. Riordan was to be the first ecclesiastical leader to introduce the "Munich Style" of stained glass to Northern California. On August 10, 1888, the Archbishop placed his first order for thirty-eight windows with Mayer, followed by another purchase on July 20, 1889 for an additional eight windows.

Sometime during 1890, it is believed that Riordan also acquired a mix of stained and plain glazed windows for the two towers and the cellar of his new Cathedral. The total cost for approximately seventy Mayer windows, according to diocesan records, was $19,196. Miraculously, none of the cathedral's Mayer stained glass suffered damage in the 1906 earthquake and subsequent fire. It would instead, be a suspected arson fire on September 7, 1962 that completely destroyed the cathedral and all records of Riordan's transactions with the Mayer firm. Riordan apparently found Mayer designs aesthetically pleasing, because on February 9, 1913 he procured sixty-nine windows for Holy Cross Cemetery's new chapel. His purchase of Mayer windows for the German Romanesque style significantly influenced the parish priests who built new churches during his episcopate.

Riordan's affinity for Mayer windows and his aesthetic and thematic preferences established a standard for high quality, grandly ornate Bavarian stained glass. The immediate question that comes to mind is, "Why did Riordan select German windows?" It is also likely that Riordan's Chicago based architects, Egan and Prindeville, may have suggested Mayer windows for the new structure. Since window openings play a paramount structural and aesthetic role in the design of a church, the decision on stained glass needed to happen early in the architectural process. In the end, Archbishop Riordan's opinions would hold sway over that of the architects.

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, thousands of imported Bavarian windows streamed into the United States, Canada, South America, Australia, and New Zealand. The largest German producers of exported stained glass were the Franz Mayer and F. X. Zettler studios of Munich, Germany.

The phenomenal success of the Mayer and Zettler stained glass studios in the United States was largely due to the enormous increase in European Catholic immigration to the United States that in turn, fueled a construction boom of new churches, schools, convents, universities, and hospitals in order to meet the educational, spiritual, and health needs of Catholic immigrant communities. But it was more than just immigration numbers that contributed to the two glass studios' prosperity. Their reputations, technological innovations, and familiarity with Christian iconography prepared them to dominate the religious marketplace in Catholic windows. Due to the financial backing and enthusiastic encouragement of King Ludwig I (1786-1868), a liturgical revival of mural and glass painting took place during the mid nineteenth century in Munich, Germany. Superior stained glass depends (then, as now) on excellent glass quality, high-grade paints, innovative painting techniques, sophisticated kilns, and skilled artisans.

Between 1880 and 1890, Munich glass makers stopped using thin glass in favor of the more structurally sound antique glass, or pot-metal glass, that resulted in better color intensity and endurance. German craftsmen then altered the actual sequence of painting glass, resulting in a more efficient and cost effective method of producing high quality windows. From medieval times up to the nineteenth century, window cartoons took enormous amounts of time to produce because they were laboriously created by hand. With the parallel development of photography in the nineteenth century, however, the Munich studios used enlarged photographs of window cartoons to cut the glass and determine the lead lines. These innovative techniques and materials enabled the stained glass makers to develop a quasi-mass production line that met the demand for Mayer and Zettler windows in the international marketplace.

Mayer and Zettler's primary advantage lay in their sensitivity to the aesthetic and theological needs of their Catholic clients. As Catholic firms in the heart of Catholic Bavaria, their familiarity with traditional Roman Catholic imagery and iconography was unquestioned. And it was common practice in San Francisco, like elsewhere in the United States, to funnel the largest portion of ecclesiastical architectural projects to Catholic architects, contractors, stained glass studios, and suppliers of interior furnishings. When Catholic clients in San Francisco turned to Mayer and Zettler for their stained glass, they were assured that the studios had the experience, knowledge, and ability to provide a variety of Christian narratives and saints.

Approximately six hundred Mayer and Zettler windows were imported from 1888 to 1959 in Northern California alone. The largest percentage of windows came between the years of 1888 and 1912. Of the six hundred ordered, only sixty four windows were Zettler stained glass and they were installed in five Roman Catholic churches. Two Zettler sites exist in San Francisco, Saint John the Evangelist Church and Holy Cross Church. Two other Zettler churches were destroyed or torn down (Placerville and Yuba County), leaving only one extant site outside of the San Francisco Bay Area in Marysville at Saint Joseph's Church.

All other remaining windows are Franz Mayer stained glass imported for twenty Roman Catholic churches and chapels. Of these, ten sites survive and five were lost in the 1906 earthquake or by later disasters. One location's windows, Saint Francis Technical School Chapel (later renamed Saint Vincent High School), were auctioned off in December of 1966 to make room for the current Saint Mary's Cathedral on Geary Street. Two collections of Mayer stained glass, owned by Saint Mary's Hospital and the Holy Family Sisters, have the majority of their windows in storage and have a limited number of windows on public display. As of this date, the location of the two remaining sets of Mayer and one set of Zetter windows are unknown.

That Riordan found Mayer and Zettler's Romantic style attractive was not an aberration, but instead a reflection of a general trend within the American Catholic Church. Catholics during the last decades of the nineteenth century and well into the early years of the twentieth century wanted Romantic windows with idealized figures exhibiting traditional Christian iconography. The Romantic style, derived from European nineteenth century painting, is steeped in a sentimentality that is unfamiliar to us today. Yet, in their time, these sentimental windows represented the aesthetic taste of San Francisco's Catholic parishes. Catholic churches expected traditional windows illustrating saints and narratives from the Life of Christ.

All Mayer and Zettler churches do, indeed, have such subjects illustrated in their windows. But, there is more in these windows than pure Catholic visual tradition. At the end of the nineteenth century, the concept of maternal love and the relationship between mothers and their children was reinvigorated and regarded as a sacred calling. Motherhood was seen to be the finest example of God's love for his children. Since maternal love was at the core of the family, the family unit itself was a community where the care of children and other family members represented the acting out of Christian values. At the turn of the twentieth century, there was a strong desire for stained glass to emphasize maternal and familial themes in American Protestant and Catholic churches. Motifs based on family narratives endured well into the 1920s. In fact, American bishops and priests were strongly encouraged by Pope Leo XIII to devote themselves to the imitation of the Holy Family.

Familial and maternal images appear frequently in Mayer and Zettler windows in Northern California. Riordan, himself, demonstrated an inclination towards designs that depict the role of mothers with their children including those of the Virgin Mary. Records in the Mayer archives list Riordan's window selections in his purchases of 1888 and 1889. Eight windows illustrate the Life of Christ, sixteen portray the twelve Apostles, and ten depict designated saints. He also chose two large rose windows for the Cathedral's transepts that contain ornamental elements and angels.

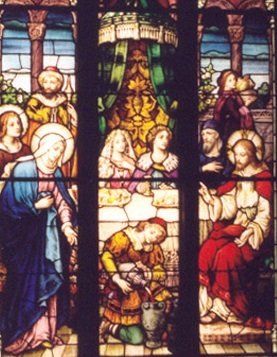

The dramatic focal point of the cathedral's interior was the enormous Assumption of Mary window set directly behind the main altar. Riordan's themes (both narrative and those of saints) are repeated in the churches who ordered Mayer or Zettler glass after 1889. Well over ninety Mayer and Zettler windows depict aspects of familial and maternal references, even those that illustrate the Life of Christ. These scenes include The Adoration, Christ Blessing the Children, Christ among the Doctors, Flight into Egypt, Holy Family, Nativity, and Presentation in the Temple. In addition, the Virgin Mary's maternal role is visually highlighted in the Instruction in Carpentry, Crucifixion, and Wedding at Cana windows. Overall, the most popular narrative was Christ Blessing the Children.

Fortunately, many Mayer and Zettler Christ Blessing the Children windows exist today (among other themes) in the churches of the San Francisco Bay Area. The second religious leader who bought Mayer stained glass was Reverend George Edward Walk of Trinity Episcopal in San Francisco who included a Christ Blessing the Children window in his fourteen Mayer windows in 1897. In 1899, Reverend John McGinty followed suit by including a Christ Blessing the Children in his selection of Zettler glass for the new Holy Cross Church. Even the Sisters of the Holy Family purchased the same theme for their nun's chapel in 1892. Both Reverend Michael Connolly (a close friend of Riordan) at Saint Paul's Church and Reverend William P. Kirby at Saint Agnes installed a Christ Blessing the Children window in their baptisteries during 1908. In Berkeley, Reverend Doctor Harry Morrison of Saint Joseph the Worker Church purchased the same theme in 1910 and Reverend P. McGuire of the Most Holy Redeemer Church in San Francisco followed suit in 1912.

Mayer and Zettler Christ Blessing the Children windows retained their popularity in San Francisco well into the 1920s and 1930s. When Reverend Francis P. McElroy built Most Holy Rosary Chapel and the Dominican Sister's Chapel at Saint Vincent's School in San Rafael in 1927, he included an oversized version of Christ Blessing the Children in the choir loft. As late as 1932, the Sisters of Mercy imported a Christ Blessing the Children window for the chapel at Saint Mary's Hospital.

Remarkably, every church that contains Mayer or Zettler stained glass was a mixed ethnic congregation thereby resulting in a rich variety of saint windows. Irish, German, French, Italian, and Spanish saints exist along side the twelve Apostles. The most frequently occurring saints are Saint Catherine of Siena, Saint Francis of Assisi, Saint Patrick and Saint Cecelia. Lesser numbers of windows depict Saint Rose of Lima, Saint Jane d'Aza, Saint Charles Borromeo, Saint Gerard Majella, Saint Columbkille, and Saint John Vianney. Between Mayer and Zettler, thirty eight different saints were depicted in their windows in Northern California.

Today, the largest collections of Mayer windows exist at Saint Paul's Church in San Francisco, at Most Holy Rosary Chapel at Saint Vincent's School in San Rafael and at Saint Vincent de Paul Church in Petaluma. The least number of narrative windows and the most extensive and varied saint windows exist at Saint Vincent de Paul. Although Saint Paul's has the most number of Mayer windows, both Saint Paul's Church and Most Holy Rosary Chapel have similar designs and narratives. The largest extant Zettler collection exists at Saint John the Evangelist Church in San Francisco.

Whether the central scene in a Mayer or Zettler window illustrates a saint or a biblical story, familial and maternal aspects are found in the figure's faces and embraces. The interior scene is always dramatically encased in an intricate architectural or lush foliage glass borders that are typical of Bavarian stained glass. Mayer and Zettler windows deliver a visual message about what mattered to Catholic parishes at the turn of the twentieth century. They speak to us about how people felt, what they believed, and what moved them. The message is received by viewers in the transformed light that passes through colored glass. The gift of Mayer and Zettler to the archdiocese was great.

This article, from June 2003, was one in a series of articles to mark the 150th anniversary of the Archdiocese of San Francisco. Jeffrey Burns, an archivist and author of a history of the Archdiocese of San Francisco, coordinated the series.

April 2024

31

8am Mass for Easter Sunday

9:30am Easter Sunday Mass, hospitality follows (coffee & donuts)

1

2

9:30am Our Spiritual Journey: rectory

7pm Baptism Preparation Class at Rectory

3

4

5

First Friday

8:30am Daily Mass in Chapel, followed by Stations of the Cross

2:30pm Eucharistic Adoration - Church

Show all

6

2nd Collection: Preservation Fund

3:30pm Reconciliation (Confession)

4:30pm Vigil Mass

Show all

7

2nd Collection: Preservation Fund

8am Mass

9:15am Mass, hospitality follows (coffee & donuts)

Show all

8

9

10

11

12

8:30am Daily Mass in Chapel, followed by Stations of the Cross

13

3:30pm Reconciliation (Confession)

4:30pm Vigil Mass

14

8am Mass

9:15am Mass, hospitality follows (coffee & donuts)

15

16

17

18

19

8:30am Daily Mass in Chapel, followed by Stations of the Cross

20

3:30pm Reconciliation (Confession)

4:30pm Vigil Mass

21

8am Mass

9:15am Mass, hospitality follows (coffee & donuts)

22

23

24

25

26

8:30am Daily Mass in Chapel, followed by Stations of the Cross

27

3:30pm Reconciliation (Confession)

4:30pm Vigil Mass

28

8am Mass

9:15am Mass, hospitality follows (coffee & donuts)

29

30

1

2

3

First Friday

2:30pm Eucharistic Adoration - Church

4

2nd Collection: Preservation Fund

3:30pm Reconciliation (Confession)

4:30pm Vigil Mass w/ Blessing of Throats

Show all